What is dyspnea (shortness of breath)?

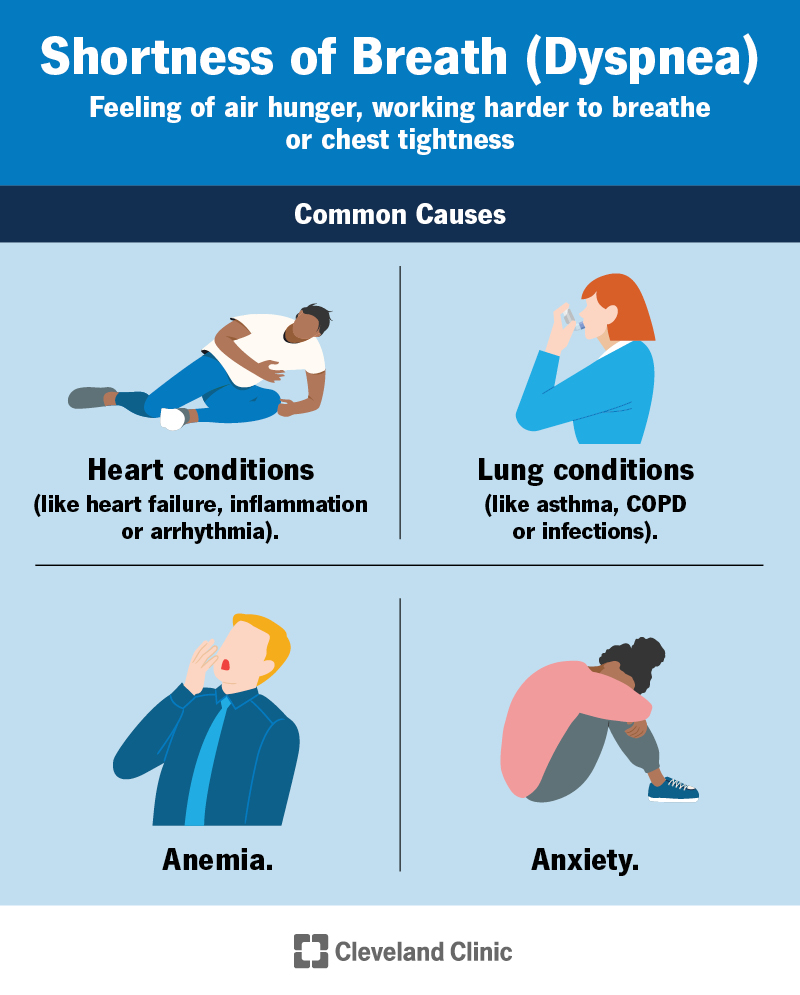

Dyspnea (pronounced “DISP-nee-uh”) is the word healthcare providers use for feeling short of breath. You might describe it as not being able to get enough air (“air hunger”), chest tightness or working harder to breathe.

Shortness of breath is often a symptom of heart and lung problems. But it can also be a sign of other conditions like asthma, allergies or anxiety. Intense exercise or having a cold can also make you feel breathless.

What are paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) and sighing dyspnea?

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) is a feeling like you can’t breathe an hour or two after falling asleep. Sighing dyspnea is when you sigh a lot after taking deep breaths in to try to relieve the feeling of dyspnea.

What is the difference between dyspnea and shortness of breath?

Dyspnea and shortness of breath are the same. Dyspnea is the medical term for the feeling of not being able to get enough air.

What are acute and chronic dyspnea?

Acute and chronic dyspnea differ in how quickly they start and how long they last. They have different causes.

Acute dyspnea

Acute dyspnea can come on quickly and doesn’t last very long (hours to days). Allergies, anxiety, exercise and illness (like the common cold or the flu) can cause acute dyspnea. More serious conditions, like a heart attack, sudden airway narrowing (anaphylaxis) or blood clot (pulmonary embolism) can also cause acute dyspnea.

Chronic dyspnea

Chronic dyspnea is shortness of breath that lasts a long time (several weeks or longer) or keeps coming back. Ongoing health conditions like asthma, heart failure and COPD can cause chronic dyspnea. Not getting enough exercise can also make you feel breathless all the time because your muscles are trying to get more oxygen.

Who gets dyspnea?

As it has so many causes, shortness of breath is very common. But you might be more likely to get short of breath if you don’t get enough exercise or have:

- Anemia (low level of red blood cells).

- Anxiety.

- Heart, lung or breathing problems.

- A history of smoking.

- A respiratory infection.

- A body mass index (BMI) over 30 (have overweight).

What are the signs of dyspnea?

Shortness of breath can feel different from person to person and depending on what’s causing it. Sometimes, it comes with other symptoms.

Some signs of dyspnea include:

- Chest tightness.

- Feeling like you need to force yourself to breathe deeply.

- Working hard to get a deep breath.

- Rapid breathing (tachypnea) or heart rate (palpitations).

- Wheezing or stridor (noisy breathing).

What causes shortness of breath (dyspnea)?

Exercise, illness and health conditions can cause shortness of breath. The most common causes of dyspnea are heart and lung conditions.

How do heart and lung conditions cause shortness of breath?

Your heart and lungs work together to bring oxygen to your blood and tissues and remove carbon dioxide. If one or the other isn’t working right, you can end up with too little oxygen or too much carbon dioxide in your blood.

When this happens, your body tells you to breathe harder to get more oxygen in or carbon dioxide out. Anything that makes your body need more oxygen — like a good workout or being at high altitudes — can also make this happen.

Your brain can also get the message that your lungs aren’t working right. This might make you feel like you’re working harder to breathe or give you a feeling of tightness in your chest. Causes for this include:

- Irritation in your lungs.

- Restriction in the way your lungs move when you breathe.

- Resistance in air movement into your lungs (from blocked or narrow airways).

What health conditions cause shortness of breath (dyspnea)?

Heart or lung disease and other conditions can cause shortness of breath.

Lung and airway conditionsHeart and blood conditionsOther conditions

• Asthma.

• Allergies.

• Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

• Respiratory illness (like bronchitis, COVID-19, the flu or other viral or bacterial infections).

• Pneumonia.

• Inflammation (pleurisy) or fluid (pleural effusion) around your lungs.

• Fluid (pulmonary edema) or scarring (fibrosis) inside your lungs.

• Lung cancer or pleural mesothelioma.

• High blood pressure in your lungs (pulmonary hypertension).

• Tuberculosis.

• Partial or complete collapsed lung (pneumothorax or atelectasis).

• Blood clot (pulmonary embolism).

• Choking.

• Anemia.

• Conditions that affect your heart muscle (cardiomyopathy).

• Abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia).

• Inflammation in or around your heart (endocarditis, pericarditis or myocarditis).

• Anxiety.

• Injury that makes breathing difficult (like a broken rib).

• Medication. Statins (cholesterol-lowering drugs) and beta-blockers (used to treat high blood pressure) are two types of medications that can cause dyspnea.

• Extreme temperatures (being very hot or very cold).

• Body mass index (BMI) over 30.

• Lack of exercise (muscle deconditioning).

• Sleep apnea can cause paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND).

How do I know what’s causing my shortness of breath?

To try to figure out what’s causing your dyspnea, your healthcare provider will perform a physical exam, including listening to your lungs with a stethoscope and taking your blood pressure. They’ll put a sensor on your finger to see how much oxygen you have in your blood.

They may also do additional testing, including:

- Chest X-ray, CT scans or other special imaging tests. Your provider can use pictures of the inside of your chest to know if there’s an issue with your lungs.

- Blood tests. Your provider can use blood tests to look for anemia or illnesses.

- Lung function tests. Tests that indicate how well you’re breathing.

- Cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Your provider will have you use a treadmill or stationary bike for this test. The tests can tell your provider the amount of oxygen you take in and carbon dioxide you let out during exercise.

How is shortness of breath (dyspnea) treated?

How you treat shortness of breath depends on what’s causing it. If you have an underlying medical condition, you’ll need to address it for your symptoms to improve.

Treatments that can improve your breathing include:

- Exercise. Exercise can strengthen your heart and lungs so they don’t have to work as hard.

- Relaxation techniques. Your provider can give you relaxation techniques and breathing exercises to practice. These can help with dyspnea from underlying breathing conditions, as well as anxiety.

- Medication. Inhaled drugs called bronchodilators can relax your airways and are prescribed for asthma and COPD. Medication to relieve pain or anxiety can help with breathlessness.

- Oxygen therapy. Your healthcare provider will prescribe extra oxygen if your blood oxygen level is too low. It’s delivered through a mask or tube in your nose.

Can dyspnea be cured?

Most people experience shortness of breath occasionally. You can usually treat what’s causing dyspnea, but it may come back, especially if you have an underlying condition.

How can I prevent shortness of breath?

You can help prevent shortness of breath by:

- Making a care plan with your provider to manage any underlying conditions and sticking to it. This includes what kind of medications to take and when to take them, exercise plans, breathing treatments and any other treatment recommended by your provider.

- Avoiding inhaling chemicals that can irritate your lungs, like paint fumes and car exhaust.

- Practicing breathing exercises or relaxation techniques.

- Not smoking.

- Maintaining a weight that’s healthy for you.

- Avoiding activity when it’s very hot or very cold or when humidity is high. If you have lung disease, look for air pollution (ozone) alerts (you can usually find them with the weather forecast). Avoid being outside when air pollution is high.

When should I see a healthcare provider?

Contact a healthcare provider if you have severe shortness of breath or if your breathlessness interferes with your everyday activities. Sometimes, shortness of breath is a sign of a medical emergency that requires immediate treatment.

If you have a condition that makes you short of breath often, ask a healthcare provider if there are additional treatments to help you breathe better.

Is dyspnea life-threatening?

Dyspnea on its own usually isn’t dangerous, but sometimes, shortness of breath can be a sign of a life-threatening condition. Go to the nearest ER if you have:

- Sudden difficulty breathing.

- Severe breathlessness (can’t catch your breath).

- Breathlessness after 30 minutes of rest.

- Blue skin, lips or nails (cyanosis).

- Chest pain or heaviness.

- Fast or irregular heartbeat (heart palpitations).

- High fever.

- Stridor (high-pitched sound) or wheezing (whistling sound) when breathing.

- Swollen ankles or feet.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

When something “takes your breath away,” it’s usually a good thing. But the scary feeling of dyspnea is the kind of breathtaking no one wants to experience. If you have sudden or severe shortness of breath, especially if you’re also having other symptoms, like nausea, chest pain or blue skin, lips or nails, go to the nearest ER.

If you’re living with shortness of breath on a regular basis due to an underlying condition, talk to your healthcare provider about managing your symptoms. You might not be able to get rid of your symptoms completely, but sometimes, even small changes can make a big difference in your quality of life.